At 9:00 a.m., I was supposed to start writing this article. At 9:07, I was refilling my coffee. At 9:24, I was reorganizing my browser tabs. It’s now 10:16, and I’ve finally begun. This may sound like procrastination. And in some ways, it is. But it’s also something else: a quiet rebellion against schedules that never seemed to work for me.

If you’re the kind of person who breaks out in stress just seeing a time-blocked calendar, you’re not alone. Despite the explosion of productivity tools and morning routine videos, many people find rigid schedules suffocating rather than helpful [1].

And the good news? There’s another way.

Why Traditional Scheduling Fails Some Brains

The classic advice—plan your day, block your hours, stick to it—assumes that humans operate like machines. But we don’t. Our energy, focus, and motivation fluctuate throughout the day and week. And for some, especially those with ADHD tendencies or creative temperaments, strict time constraints can feel paralyzing rather than empowering [2].

This isn’t laziness. It’s a mismatch between the tool (rigid scheduling) and the user (you). In fact, research shows that self-determined work rhythms often lead to higher satisfaction and performance, especially in creative and knowledge-based roles [3].

It turns out that time management doesn’t have to mean time domination. Sometimes, it means knowing when not to force it.

The Case for Anti-Schedule Productivity

In 2013, designer and entrepreneur Paul Jarvis popularized the idea of the “anti-schedule”—a flexible system where you prioritize outcomes over hours. Instead of blocking time to do something, you focus on what needs to get done and leave room for when you’re best able to do it [4].

This isn’t a lack of structure. It’s just structure based on priorities, not clocks.

For example:

-

Instead of “Write blog post from 2–3 p.m.,” try “Write blog post sometime today after I’ve had lunch.”

-

Instead of scheduling a 10 a.m. workout, try “Workout when I feel restless or stuck.”

It’s a subtle shift—but for people who resist micro-managing their own time, it’s a powerful one.

A Real Anti-Schedule Day (Example)

To make this concrete, here’s what an anti-schedule might look like:

8:00 a.m.: Wake up, coffee, journal (not scheduled—just natural rhythm) 9:15 a.m.: Energy feels high → begin first draft of blog post 10:45 a.m.: Fatigue → break, walk, email check 12:00 p.m.: Lunch 1:30 p.m.: Feeling creative again → brainstorm project ideas 3:00 p.m.: Distraction kicks in → clean workspace, listen to podcast 4:30 p.m.: Unexpected focus surge → finalize proposal

No alarms, no pressure. Just flow, gently directed by priorities.

What If You Work a 9-to-5?

Flexibility sounds great—until your calendar is filled with meetings, check-ins, and tight deadlines. But even within traditional jobs, the anti-schedule mindset can be adapted.

Here’s how:

-

Batch deep work into quieter hours—mornings or late afternoons often work best.

-

Propose asynchronous work for tasks that don’t need real-time collaboration.

-

Use "soft blocks": Instead of “Finish report 10–11 a.m.,” try “Finish report before lunch.”

You’re not ignoring structure—you’re adapting it to better reflect how your brain actually works.

Mapping Your Natural Productivity Curve

So how do you know when to do what, if not by schedule?

Try this simple experiment for three days:

-

Log when you feel alert, distracted, creative, tired.

-

Track what kinds of tasks felt easier or harder at different times.

-

Look for patterns: maybe you write best before 11 a.m., or do admin best when you're slightly tired.

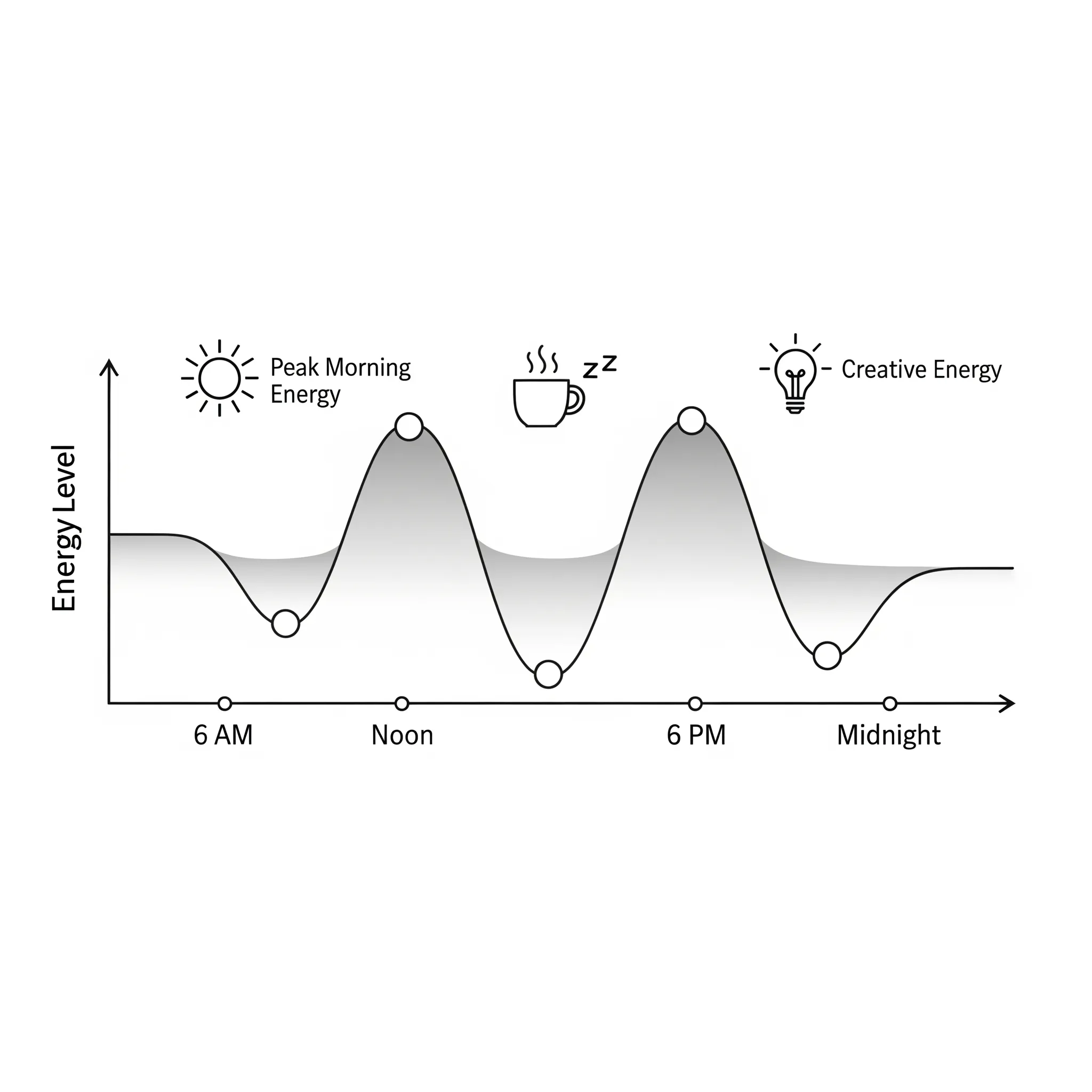

Many of us follow “ultradian rhythms”—90–120 minute cognitive cycles—with natural peaks and dips throughout the day [5]. Learning your rhythm gives you a personalized map of focus zones, without needing to micromanage the clock.

Three Gentle Tools for Structure (Without a Straitjacket)

-

The Daily 3 List: Choose three important things to get done. Don’t assign them a time—just keep them visible, and tackle them when it feels right [6].

-

Energy Anchors: Instead of a full routine, try light structure points—like a walk after lunch or journaling in the morning. These become anchors that give your day shape, without rigidity.

-

“Done” Lists Instead of To-Do Lists: Keep a list of what you actually did. It creates motivation and gives you credit for progress, even if your day didn’t follow a plan [7].

Why We Feel Guilty About Being Unscheduled

Even if this all makes sense, you might still feel uncomfortable. Why?

Because we’ve absorbed the idea that structure equals virtue. From school bells to work calendars, we’re trained to believe that busy = good, planned = responsible. Choosing to work on your own terms can feel indulgent—even if you’re getting more done.

But here’s the truth: productivity isn’t morality. It's a method. And it's yours to reshape.

Flexibility Isn’t Laziness: What the Brain Says

Neuroscientific research supports the idea that attention operates in cycles, not constant states. Forcing concentration during a cognitive “low tide” often leads to frustration or burnout [8].

Psychological studies also show that people who have greater autonomy over when they work experience better results and higher engagement—particularly in creative or cognitively demanding jobs [9].

In other words, you’re not the problem—your system might be.

Final Thoughts: Attention, Not Control

Most of us were taught that time management means controlling time. But really, it’s about managing your attention and energy. You can’t always predict when you’ll be “in the zone,” but you can create the conditions that make it easier to get there.

You don’t need to time-block your life into submission. You need a way of working that respects your natural rhythms, your values, and your mind.

Ironically, it’s in letting go of rigid control that many people finally get their time—and attention—back.

References

-

Newport, C. (2016). Deep Work. Grand Central Publishing.

-

Barkley, R. A. (2015). Taking Charge of Adult ADHD. Guilford Press.

-

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. Riverhead Books.

-

Jarvis, P. (2013). “The Anti-Schedule.” pjrvs.com

-

Kleitman, N. (1963). Sleep and Wakefulness. University of Chicago Press.

-

Forster, M. (2006). Do It Tomorrow and Other Secrets of Time Management. Hodder & Stoughton.

-

Krug, D. (2019). Build Your Done List. Personal blog.

-

Huberman, A. (2022). “Controlling Your Dopamine for Motivation, Focus & Satisfaction.” Huberman Lab Podcast.

-

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). “The ‘What’ and ‘Why’ of Goal Pursuits.” Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.