There is no shortage of advice on how to “get more done.” Search the shelves or scroll online and you will find dozens of systems, apps, and routines promising to fix distraction, procrastination, and low output. The trouble is that many people discover the promise of productivity becomes a second job: tweaking apps, optimizing routines, tracking habits, and comparing dashboards. That busywork can feel productive but often produces little real progress.

It is worth considering that the problem is not how much effort you apply. It is how the work is structured. A lot of the visible hustle is compensating for weak systems. If you build better systems, you will usually get the results you want with less pushing.

Why “more productivity” often backfires

Productivity advice frequently focuses on individual tactics: batching email, the perfect morning ritual, or a new to-do app. Those tactics can help, but the missing step is designing the environment and the process so that the same good behavior happens routinely, without constant attention.

Cognitive science helps explain why this matters. When people switch between different tasks, performance suffers because the brain pays a measurable switching cost. Task-switching research documents slower responses and more errors when people alternate tasks rather than focus on one at a time. This effect is one reason fragmented days feel less productive, even when they feel busy.[1],[2]

There is also the problem of decision fatigue. Laboratory research finds that making many choices impairs subsequent self-control and active initiative. The repeated low-stakes decisions of daily life can drain the energy needed for deeper work. Systems that reduce repeated decisions therefore preserve mental resources for the work that matters most.[3]

What I mean by “system”

A system is more than a habit. A habit is a single repeated action. A system is a predictable pipeline that turns inputs into outputs. It has three parts: inputs, a repeatable process, and a predictable outcome. Good systems make behavior reliable without constant oversight.

This is the same insight behind classic operating procedures and popular productivity frameworks. For example, David Allen’s Getting Things Done popularized the idea of centralizing capture. A single place to gather all inputs before deciding what to do next, which is a system design choice, not a trick.[4]

Systems work because they change the environment

Systems matter because they change where the cognitive work happens. Instead of relying on willpower or constant prioritization, you design an environment that nudges the right next action. The medical world provides a stark example. A short, structured surgical safety checklist implemented across multiple hospitals was associated with substantial reductions in complications and perioperative death. The checklist is not a substitute for skill. It is a simple system that ensures key steps happen, reliably. That project is a clear demonstration of systems outperforming heroics alone.[5],[6]

The practical payoff, not the metaphor

Here is a practical truth readers want to test: improving a system often compounds better than adding effort. Automations and standardized routines allow one improvement to apply across many occurrences. That is why scripts or templates matter. You spend an hour building a tool and then reap time back every week.

A helpful principle is modularity. Tiago Forte calls this “intermediate packets”: small reusable components you assemble into larger work. That pattern makes systems composable and maintainable across projects.[7]

A six-step recipe to design better systems

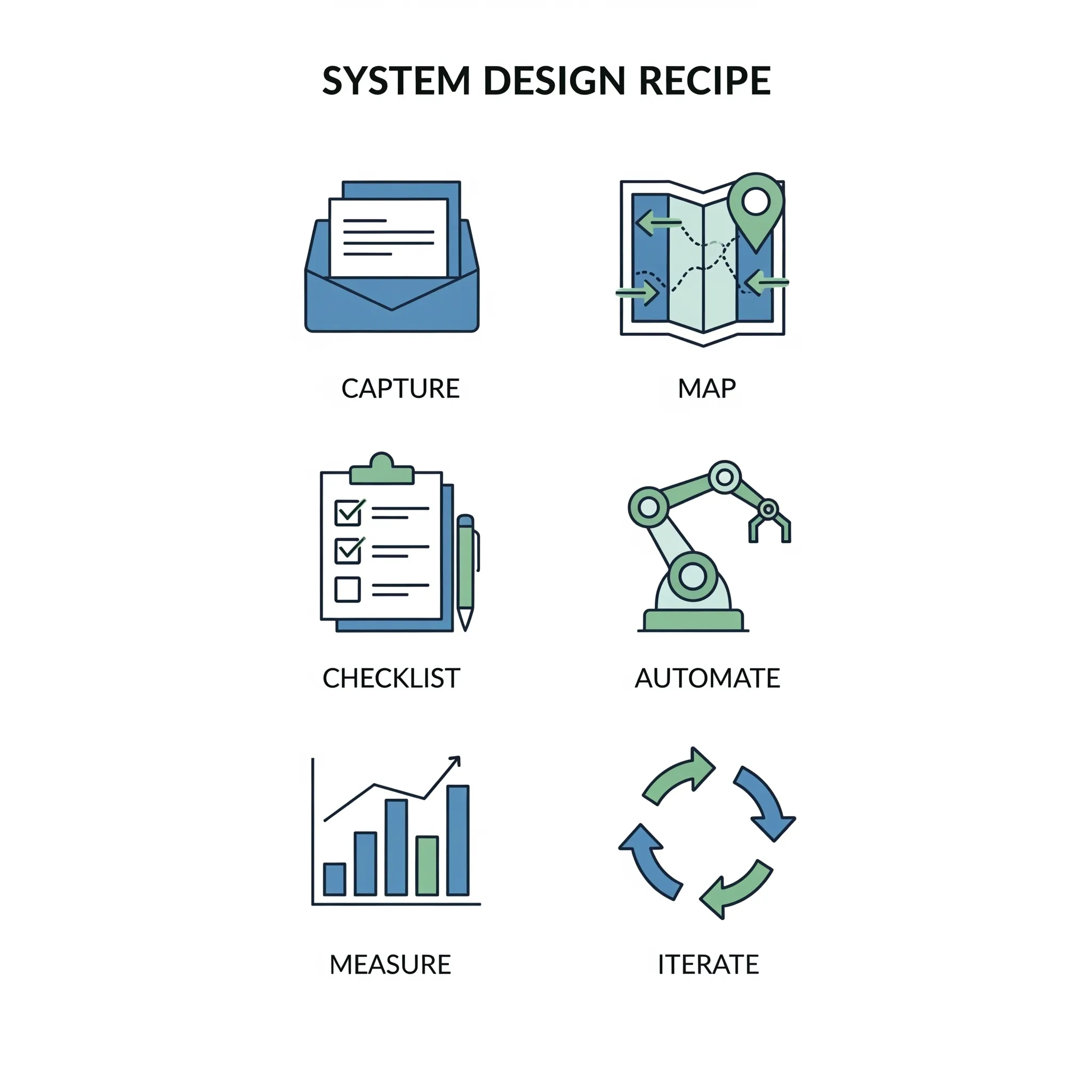

Try this pragmatic path. It is intentionally small and iterative.

-

Capture: Centralize inputs in one place. If ideas, requests, or tasks appear in ten different places, nothing gets done. Use a single inbox for two weeks and observe the flows.[4]

-

Map: Sketch the end-to-end steps for a frequent output (publish an article, onboard a client). Keep it short, five to eight steps.

-

Standardize: Turn step sequences into checklists or templates so people repeat the same high-value actions. Checklists have strong evidence in high-risk fields.[6]

-

Automate the low-risk pieces: Choose one repeatable manual step to automate. If it saves five minutes and it happens ten times a week, build it.

-

Measure: Pick one metric (hours saved, errors prevented, or dollars avoided) and track it for a month. Use the simple ROI formula below.

-

Iterate: Schedule a short review and adjust. Systems are not “set and forget.” They need feedback.

A simple ROI formula readers can use right away

You can make choices defensible with a small arithmetic test. Use this formula:

Annual value = (time saved per occurrence) × (occurrences per year) × (value per hour)

For example, a 10-minute automation that runs five times per week saves about 43 hours per year. If you value your hour at 30 euros, that automation is worth approximately 1,290 euros per year before subtracting the cost of building it. Being explicit like this helps you choose where to invest effort.

Common reader traps and how to avoid them

-

Over-engineering: Building a perfect system before testing it. Fix this by starting with a “minimum useful system” and run a short experiment.

-

Automation debt: Automating brittle processes that change frequently. Avoid by automating only the stable parts and keep a rollback plan.

-

Social buy-in failure: Systems often fail for social reasons. Make adoption easy and explain the interpersonal benefits (less firefighting, clearer handoffs).

-

Mistaking optimization for progress: Optimizing how you send email will not replace a bad product. Use systems to remove friction so you can focus on the actual high-leverage work.

Cal Newport’s recent critique of “productivity theater” is a useful reminder that visible busyness is no substitute for deliberate, slow improvement in how work is organized. Systems should reduce the need for constant busywork.[8]

A 3-week system sprint you can run this month

Week 0, preparation: Pick one recurring output (a weekly report, a blog post, invoices). Map it on one page. Week 1, prototype: Implement the six-step recipe with minimal automation (one checklist, one template). Run it. Week 2, measure and iterate: Apply the ROI formula, collect qualitative feedback, and fix the highest friction point. Week 3, stabilize or rollback: If the system wins, document it; if not, roll back and capture lessons.

This small commitment reduces the psychological barrier for readers. Most will discover a tangible time or quality gain in three weeks.

Case studies that translate well

-

High-stakes systems: The WHO/NEJM surgical checklist shows how a short procedural system reduced complications and deaths across diverse settings. The lesson is that simple, well-executed steps scale.[5],[6]

-

Solo creator system: A content pipeline of idea capture, scheduled drafting, editing slot, and publishing cadence turns inconsistent output into reliable throughput. Breaking posts into “intermediate packets” makes edits and repurposing cheap.[7]

Mini FAQ

How do I tell a system from a habit? A habit is one repeated action. A system is a repeatable process that turns inputs into outputs. For example, using a calendar reminder is a habit; having a workflow to plan, draft, and publish content is a system.

How do I design a system that actually reduces work, not just shifts it? Measure time spent before and after implementing a system. Automate only stable, repetitive steps and avoid adding complexity that requires extra maintenance.

What small first step gives the largest return? Centralizing input capture is often high-return. Many people lose time hunting for information scattered in email, chat, and notes.

How do I measure if a system is working? Pick one metric such as hours saved, error rate, or revenue impact. Use the ROI formula to quantify gains and costs.

When do systems become brittle or bureaucratic? When they are over-engineered or lack feedback loops. Review systems regularly and keep them simple.

What should I automate and what should stay human? Automate stable, low-risk, repeatable tasks. Keep decision-heavy or creative tasks human.

How do I get others to respect and use my system? Involve them early, communicate benefits clearly, and keep systems easy to adopt.

Are there proven examples that show systems beat hustle? Yes. The surgical safety checklist reduced mortality worldwide. Similarly, content creators find structured pipelines improve output without burnout.

Do systems kill creativity? Not if designed thoughtfully. Systems handle routine parts so mental energy is freed for creativity.

How do I recover from a failed system? Roll back quickly, document lessons, and try a simpler approach.

Conclusion: focus on structure, not hustle

If you are tired of trying one productivity tip after another, step back and design a system. Start small, measure clearly, and pick the correct thing to automate. Systems are not glamorous, but they quietly multiply your time and impact.

The real promise is simple: when the system works, you do less pushing and get more done.

Short checklist to get started

-

Pick one repeatable output you care about.

-

Map the 5 to 8 steps on a single page.

-

Create a one-page checklist and one template.

-

Automate one low-risk task.

-

Measure one metric for 3 weeks.

-

Iterate or rollback.

References

[1] Rubinstein, J. S., Meyer, D. E., & Evans, J. E. (2001). Executive Control of Cognitive Processes in Task Switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. [2] American Psychological Association. Multitasking: Switching costs (summary referencing David Meyer’s remarks and task-switching costs). [3] Vohs, K. D., et al. (2008). Making Choices Impairs Subsequent Self-Control: A Limited-Resource Account. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. [4] Allen, D. (2001). Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity. Penguin. [5] Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. (2009). A Surgical Safety Checklist to Reduce Morbidity and Mortality in a Global Population. New England Journal of Medicine. [6] Gawande, A. (2010). The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. Metropolitan Books. [7] Forte, T. (2022). Building a Second Brain. Forte Labs. [8] Newport, C. (2021). A World Without Email: Reimagining Work in an Age of Communication Overload. Portfolio.